Selecting the Right Laser & Process Parameters

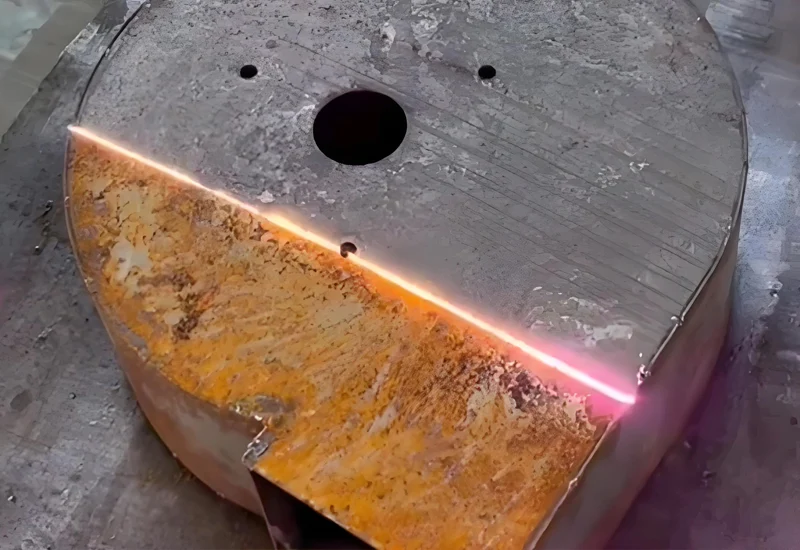

Laser cleaning is a powerful tool—but only when precisely tuned. The effectiveness, efficiency, and safety of any laser cleaning process depend on correctly selecting and balancing multiple laser and scanning parameters. These variables directly control how much energy reaches the surface, how that energy is delivered, and how well the system discriminates between the contaminant and the substrate.

To achieve optimal results—maximum contaminant removal with zero or minimal substrate damage—it is essential to tailor the following key parameters to the specific material, contaminant type, and surface condition: wavelength, pulse width, fluence, repetition rate, and scan speed.

Wavelength

The wavelength defines the color (or more technically, energy level) of the laser beam and directly influences how the material absorbs the energy.

Infrared (1064 nm, Nd:YAG or fiber lasers): Effective for metals and oxides, where rust or contaminants absorb more energy than the base metal.

Green (532 nm): Offers better absorption in certain paints, polymers, and printed circuit board coatings.

UV (355 nm, excimer lasers): Best for organic materials, thin films, and delicate surfaces like plastics or electronics.

Key Principle: Choose a wavelength that is highly absorbed by the contaminant, but minimally absorbed by the substrate, ensuring selective removal.

Pulse Width (Pulse Duration)

Pulse width defines how long each laser pulse lasts—typically measured in nanoseconds (ns), picoseconds (ps), or femtoseconds (fs). It determines how rapidly energy is delivered.

Nanosecond Lasers (ns): Common in industrial cleaning; effective for rust, paint, and scale, but can cause slight thermal effects.

Picosecond Lasers (ps): Deliver energy faster, with less heat transfer into the substrate—ideal for precision applications.

Femtosecond Lasers (fs): Ultrashort pulses that create a “cold ablation” effect—excellent for heat-sensitive materials or micro-scale surfaces.

Shorter pulse durations reduce heat diffusion, minimizing the heat-affected zone (HAZ) and preserving substrate integrity, especially on reflective or low-melting materials.

Fluence (Energy Density)

Fluence is the amount of energy delivered per unit area per pulse (Joules per cm²). It is one of the most critical parameters for determining cleaning effectiveness.

Low Fluence (<1 J/cm²): May be insufficient to ablate the contaminant, or only clean lightly adhered materials.

Moderate Fluence (1–5 J/cm²): Effective for most common contaminants such as rust, oxides, and paint.

High Fluence (>5 J/cm²): Required for thick or stubborn layers, but risks damaging the substrate if not properly controlled.

Optimal fluence depends on the contaminant’s bond strength and thermal properties. Exceeding the ablation threshold ensures cleaning, but should not exceed the substrate’s damage threshold.

Repetition Rate (Pulse Frequency)

Repetition rate refers to how many laser pulses are emitted per second, typically measured in kilohertz (kHz).

Low Repetition Rates (<10 kHz): Higher energy per pulse but slower throughput; useful for precise, deep cleaning.

High Repetition Rates (10–200+ kHz): Enable faster cleaning speeds but reduce individual pulse energy; useful for lighter contamination and large-area coverage.

Trade-Off: Higher repetition improves productivity but can increase cumulative heat load. Repetition rate must be balanced with scan speed and cooling time.

Scan Speed

Scan speed is the rate at which the laser beam moves across the surface, typically in mm/s or m/min. It directly influences how much energy is delivered to a given area.

Slower Scan Speeds: More energy per unit area; better for thick or tough contaminants, but with higher risk of substrate heating.

Faster Scan Speeds: Less dwell time; ideal for thin layers, high-value surfaces, or low-tolerance components.

Optimization Tip: Scan speed must be matched to the repetition rate and spot overlap to ensure uniform coverage without overexposure.

Laser cleaning is not just about pointing a laser and firing—it’s a fine-tuned engineering process. Selecting the right combination of laser and process parameters is essential to ensuring high cleaning performance with minimal risk.

Wavelength controls material-specific absorption.

Pulse width governs how sharply energy is delivered.

Fluence determines ablation power.

Repetition rate affects processing speed and thermal buildup.

Scan speed balances energy delivery and surface coverage.

Each parameter influences the others. For any successful application—whether cleaning rust from steel, stripping paint from aluminum, or removing film from ceramics—these settings must be carefully optimized based on material properties, contaminant characteristics, and required precision.

When correctly configured, laser cleaning becomes a highly efficient, non-contact, and selective process suitable for even the most demanding environments.

0531-87978823

0531-87978823 +86 16653132325

+86 16653132325 sales01@raytu.com

sales01@raytu.com Contact us

Contact us